Sunset over Lake Cameron

Where we live now is, geographically, a river valley. The Potomac River is only about 8 miles from here, and the little lake just beyond our windows is part of a creek system, Sugarland Run, that winds its way into the Potomac; so, yes, we live in the Potomac Valley. But ask people who live around here if they live in a river valley, and most will look at you as if you just asked them if they live on the moon.

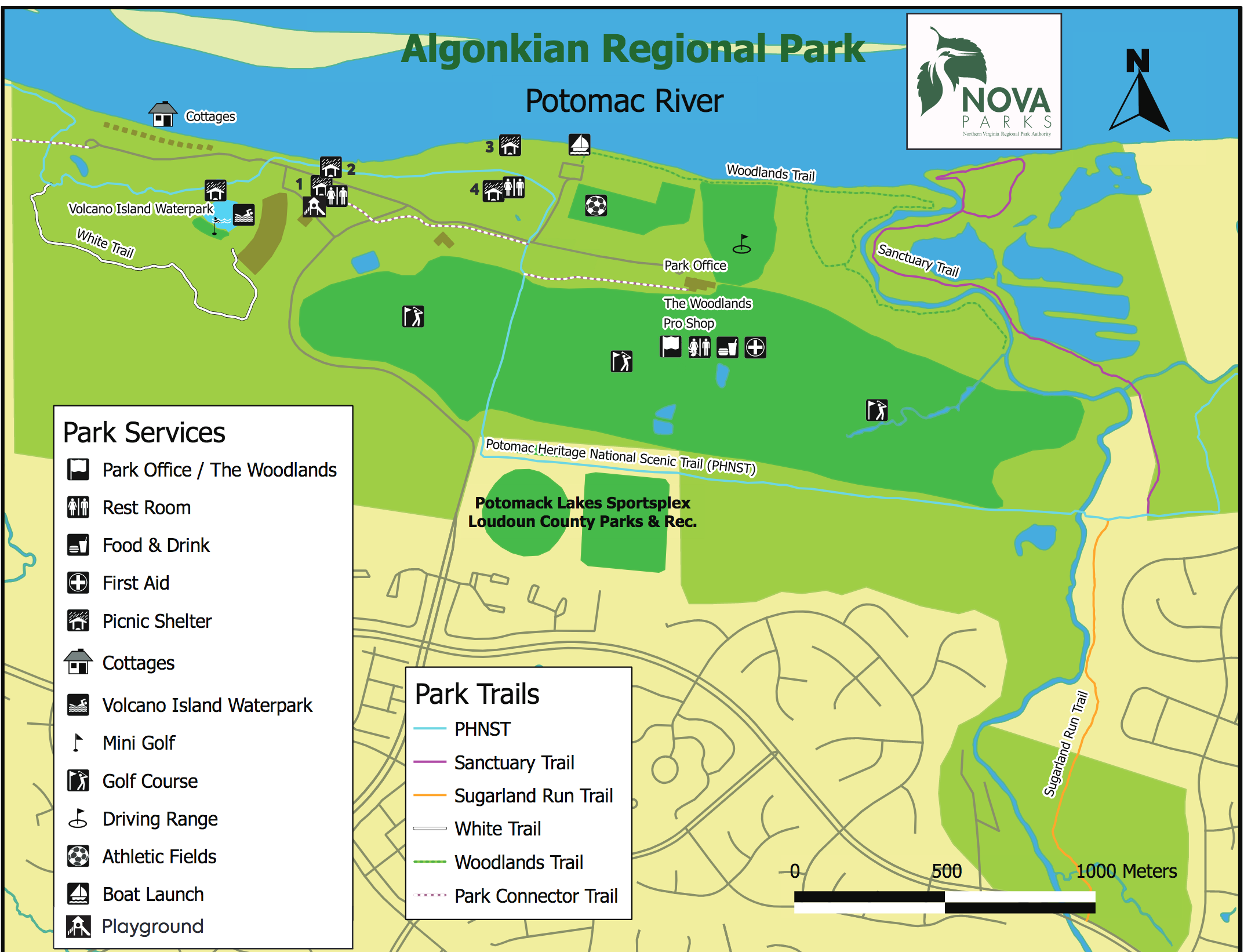

Algonkian Regional Park, where Sugarland Run enters the Potomac

Why? Because Northern Virginia is a dizzying maze of roadways, housing developments, office parks, schools, hospitals, and shopping hubs, all reached by the speeding (or crawling) cars that careen among them. The drivers are focused–and must be–on their destinations of the moment, or they risk losing precious minutes out of their finely calibrated schedules. All of this hyper busyness takes place–an apt metaphor–amid a green landscape of watered hills that would be covered everywhere with trees if we would only let it be. But that’s beside the point. After all, wherever there are cities, you’ll find the same exquisitely-tuned frenzy that happens regardless of the geography. It’s no wonder that most people here don’t think of themselves as living in a river valley, because their minute-to-minute priorities don’t allow them to see the connection between the Potomac, the streams that flow into it, and themselves.

Why should they see it? How could they? When I look out my window at the shimmering small lake, I luxuriate in its mirrorglass finish, the birdsong, the trees, and the wildflowers it provides, but it’s easy for me to miss that it’s really a reservoir created by a branch of Sugarland Run, which many years ago was dammed at its north end about 100 feet above the stream bed: a stream which a person cannot see from the lake path, so cannot know that it exists. The branch itself was diverted 2 decades ago to build the local segment of the 6-lane Fairfax County Parkway, on which thousands of cars per day zip by on their necessary errands behind high walls that spare surrounding communities from the roar of passing vehicles.

Lake Cameron: outflow structure beside the hidden north end dam

Meanwhile, at the south end of our little lake/reservoir stands a cute, vine-covered bridge, which itself covers four broad pipes that carry the silent waters of Sugarland Run into the lake. The invisible pipes lie deep under a small community park and, beyond that, under a six-lane boulevard whose thousands of zipping drivers per day would never be aware that a vital stream flows beneath them.

Lake Cameron: entry from underground stream beneath this bridge

In contrast, everyone in the Sacramento Valley knows that they live in a river valley.

Not only is the Sacramento River and its miles-broad floodplain the most dominant feature of the landscape, but much of what people see as they drive the highways are the treeless fields planted in the crops that the river makes possible. Most obvious, the lack of water is the no. 1 obsession for most Northern Californians, so the Valley and the Sacramento and American rivers that have carved it are pretty much always on people’s minds.

I suspect that if drought were to strike the verdant Northern Virginia in which we now live, and if water needed to be rationed here as it is in California, then there would be here a much sharper valley consciousness in this land of the Potomac. If the waters no longer came from pipes like those under that cute little bridge, and if lake levels fell so that the waters looked like Northern California’s Folsom Lake (below) did last year, certainly Northern Virginians would become not only more aware of how the river shapes their lives, but they would also begin to focus their imaginations on solving the crisis, as Californians do.

Intensely depleted Folsom Lake Reservoir of the American River, July 24, 2021

Similarly, if the rains were to come in astounding profusion, as they have been coming–via climate change–to the Indus valleys in Pakistan and to the river valleys in nearby states like Kentucky (below), then valley consciousness would bloom here, too. If the Fairfax County Parkway were to be suddenly blocked by a flood of Sugarland Run, so that the cars could not move, then we’d all see a connection between the Potomac, the streams that flow into it, and ourselves.

But since we don’t yet have these shocks to give us a valley consciousness, we tend not to see that the bountiful water we have for all our needs, as well as for our lush green landscape, comes fully from our living in the valley of the Potomac and its tributary streams.

Sugarland Run enters the Potomac River, Algonkian Regional Park

A September Lakeside and Riverside Gallery

Playground along Lake Cameron

Horse nettle, AKA Devil’s tomato, along Lake Cameron

Goldfinch by Lake Audubon

Boats and warves along Lake Audubon

Daisy fleabane by Lake Cameron

Yellow swallowtail on Lake Audubon path

Lake Audubon woods with jogger and hiker

Canada geese on Lake Cameron boat launch

Purple heather and Goldenrod display, Lake Cameron

Male cardinal, woods beyond Lake Cameron

Nodding bur marigold display, Lake Cameron

Gray catbird by Lake Cameron

Potomac River, looking upstream, Algonkian Regional Park

Fritillary butterfly in Daisy fleabane, by Potomac River, Algonkian Regional Park

So much beauty in the Valley of the Potomac, and October is on the way. We can’t wait!

Pingback: January 2023:Watching the CaliFloods from 2500 Miles | From Sacramento to Potomac: Tales of Two Valleys