Mother’s Day display on our porch: oakleaf hydrangea, petunias, chrysanthemums

In this month’s entry:

Our First Mother’s Day in Our New Home

Saving the Colorado: Water Deal in the West

More Potomac Valley Travels Back in Time

May 2023 Photo/Video Gallery

Our First Mother’s Day in Our New Home

Three Canada geese babies snuggle with Mom on lakeside path

Jean and I celebrated our first Mother’s Day in our Virginia home not so much on the day itself, but through the opportunities we have so often now to be with our grandchildren and our East Coast children. We made a week-long visit to our children and grandchildren in Georgia this month, and we have regular visits with our 2 children and 2 grandchildren here in Northern Virginia. One of our New York children also made the visit to Georgia when we were there, so that was an added bonus.

Because May also marks the time of year when so many new young animals are born, we also have the joy of witnessing Mother- and Father-hood during our daily trips around the lake. This month’s blog entry features pics and videos of the most evident of those celebrations of new birth. It seems as if every time Jean or I goes around the lake we discover something different, surprising, and often heartwarming.

A Walk around the Lake on a Crisp May Morning

For example, on a mid-May early morning, I’m on my walk–but without my camera–and as I come over a slight ridge on the east side path, I’m surprised to see looking right at me, no more than 20 feet away, Mr. Red Fox, who is looking as startled as I am. And then he looks slightly annoyed. As I stand still, watching, he then gives me a resigned look, and casually ambles off the path into the cover of spring wildflowers along the lake. I continue on my walk and as I get to the point where he turned off the path, I look over into the greenery and there he is, just ambling ever so leisurely deeper into the cover. No anxiety, but just not wanting to be sociable. I understand his antipathy. After all, even though I am the top predator in this situation, he can tell I’m not much of a threat, so his body language is trying to tell me that he still rules the roost around here. But of course he knows that’s not true, not with all the cars and trucks roaring along the highway no more than 200 hundred yards away. We could have a nice body language conversation about being stuck together in this annoying urban maelstrom, but that’s not gonna happen. Oh well.

Red Fox eyeing me last month, perhaps posing for the camera.

I just keep ambling on in my own leisurely way, practicing my whistling to the birds, who zip on by and keep giving me lessons in whistling and singing that I’ll never come close to matching, but it’s a load of fun for me, and I hope they get a laugh out of it, too.

Then, as I come around the north end of the lake and go into the deep shade of maples, oaks, and red cedars along the west side, I’m happy to come upon one of the young families of Canada geese, who’ve been dominating lakeside culture over the past two weeks. I bet mom and dad know that Mr. Fox is out and about on the other side of the lake. The six little ones, still in their yellow fuzzy coats, are huddled together between their parents, who are ever alert scanning the lake and trees. I’m glad I don’t bother them as I stroll slowly past, not more than four feet away, saying quietly, “Don’t worry, friends, I won’t bother you. I hope you’re doing well this beautiful morning.” Dad doesn’t even turn to look toward me, as he scans the distant shore. He spies a great blue heron flying past the trees headed for another hoped-for meal.

A great blue heron eyeing a potential meal from the boat dock, west side

As the new family continues its business along the path, I’m back to strolling toward home and practicing my whistling, imagining I’m Mozart or Vivaldi trying to imitate the birdsong and laughably failing.

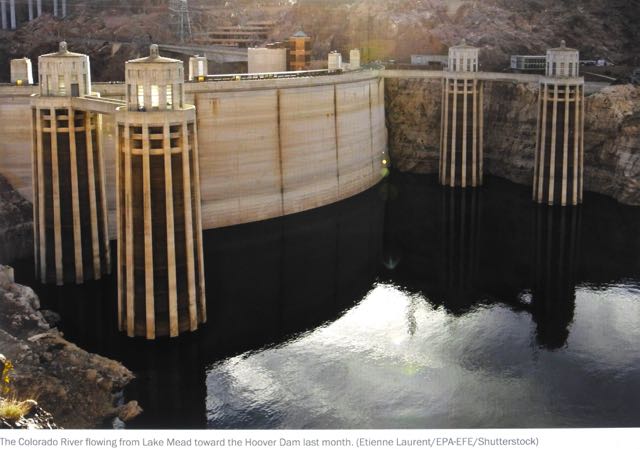

Saving the Colorado: Water Deal in the West

When Jean and I traveled from California to Arizona and then home across Nevada in March 2021, we were shocked by the steep decline in water in Lake Mead, the massive reservoir created by the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River. Lake Mead provides water and electricity to many millions across the southwest, including glittering, expanding metropolitan Las Vegas only a few miles north of the dam. Decades of worsening drought, coupled with steadily growing human demand, have now brought Lake Mead, Arizona’s Lake Powell, and the entire length of the Colorado toward becoming a “deadpool”: separated bodies of water too low even to flow. As climate change intensifies, the need for radical change in how much water is used and how it is used has become critical for all seven states through which the river or its tributaries still flow, as well as northern Mexico and the tribal lands owned by indigenous peoples in the Southwest.

As with most other environmental questions, “How to save the Colorado?” has been debated and argued over by competing politicians for years, with no real action. All seven states need to reduce their use of the river water; no one wants to give an inch. California is the oldest and largest user of the Colorado water, primarily to sustain the huge farms of the Imperial Valley, which provides produce for much of the nation in winter months. California’s negotiators have said for years that the original pact among the states, going back to 1922, still guarantees primary “water rights” to California, but that was long before state populations and industries grew to their present size and complexity, and before anyone could imagine a water crisis like today’s.

Clearly the time has come to face facts, and in early May the Biden administration stepped in to give an ultimatum and a promise: reduce water usage significantly over the next 3 years, and in exchange we’ll provide federal funds as partial compensation. After two weeks of deliberation, lo and behold, a deal has finally been reached, as announced May 24, 2023, in the Washington Post:

“The Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada agreed to conserve 3 million acre-feet of water over the next three years — amounting to 13 percent of their total apportionment — with the administration compensating them for three-quarters of the savings. This would total about $1.2 billion in federal grants from the Inflation Reduction Act.”

Of course, the devil is in the details, and all we can hope is that the state governments, local governments, the many special interests, and we citizens can actually work together with the federal government to make the sacrifices to save the water supply. Whether massive agribusiness can for once do something other than yell, sue, and stamp their feet remains to be seen. The same goes for the politicians who are lavishly gifted by those special interests. Can they for once do the right thing for us and the planet? The world will be watching for a miracle.

My 2017 aerial photo showing irrigated farmland in the Imperial Valley beside normal desert. Water usage in this region will need to be greatly reduced to save the Colorado.

More Potomac Valley Travels Back in Time

Hagerstown City Park fountain and azaleas, May 20

On Saturday, May 20, we visited another Potomac Valley city, Hagerstown, Maryland, which is named for one of its first European settlers, Jonathan Hager, a German blacksmith, furrier, and jack-of-all-trades. Hager emigrated in 1736 and built the settlement’s first substantial house in 1739 for his wife, Elizabeth. The house was restored in the 1940s and today includes a museum that attracts visitors fascinated by 18th century Maryland history. Hagerstown lies along Antietam Creek, a mere 13 miles north of the Antietam Civil War Battlefield Park, which we visited in December.

Hager House (1739) in Hagerstown, MD, City Park

Linking the Hager House to Antietam Creek is the stream that actually flows beneath the house, and which then flows into Marsh Run, a tributary of the Antietam. That vital water source made the Hagers’ entrepreneurial lives as farmers and craftspeople possible, as it did the lives of all the early settlers.

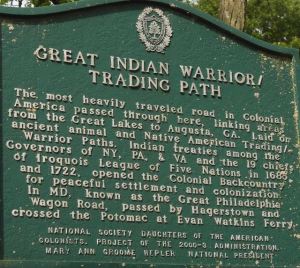

It is no coincidence that running just past the Hager House is the ancient road now known as the Great Indian Warrior/Trading Path. For thousands of years, this path linked the indigenous nations of the Northeast with those of the Southeast for trade and the flow of ideas. Inevitably–and catastrophically for the Native peoples–after European settlement, treaties between the tribes and the settlers allowed the path to become an even more crucial link for trade and travel. It eventually became one of the United States’ early highways, Route 11, which parallels today’s Interstate 81. The early path had the great advantage of being located between two dependable waterways, Antietam Creek and Conococheague Creek, both of which flow into the Potomac from the north, not far from where the Potomac’s most important tributary, the Shenandoah, flows into it from the south.

Today’s US 11 and Interstate 81 are the latest iterations of this ancient indigenous path for trade and ideas. Note the tragic irony in the claims of the treaties.

This under-house stream, linked to Antietam Creek, made the Hagers’ entrepreneurial lives possible.

May 2023 Photo/Video Gallery: Our Lake and Travels

One of our beavers drags a branch into west side lodge

This cottontail hops along the north end path and then meets three other walkers

A catbird sings out from a dead tree in the north end woods

A hungry pine siskin at our new feeder, above lake

On our Georgia trip, blue jays mob this red-shouldered hawk as our family looks on

2-week-old gosling on east bank path

Baby red-bellied cooter and two adults on east side log

Great blue heron in flight along east bank

Swimming practice: new Canada goose family

Swan swims in Hagerstown City Park lake

Two new Canada goose families on the east side path

Male red-winged blackbird on a north end reed stalk

Male cardinal on red cedar west bank

Red-bellied cooter and male mallard share east side log

One of our many members of the song sparrow choir sings “Onward to June!”