Making a connection with wildlife: Our youngest granddaughter cradles a Painted Lady butterfly, June 13

In this month’s entry:

Going to the Source: Susquehanna Journey

Williamsport to Cooperstown: Baseball, but Not Only

Ithaca and Serendipity: The Call of Birds

Amish Country: A Living Past, a Model for the Future?

The June 2024 Gallery: Potpourri

A pair of Grackles at the Susquehanna source, Cooperstown, NY, June 10

The Great River of the East: Susquehanna Journey

On a bridge above the tiny Susquehanna, we look toward its source, Otsego Lake, June 10

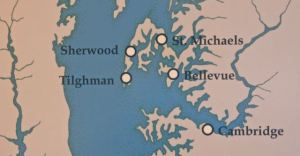

For many years, I had been tantalized by the Great River of the East Coast, the Susquehanna. The longest river east of the Mississippi, this queen of East Coast waterways winds 444 miles from tiny Lake Otsego in Cooperstown, New York, through majestic mountain gaps in Pennsylvania, and past the towns and cities that have thrived along its banks. Finally, at Havre de Grace, Maryland, the Susquehanna flows into mammoth Chesapeake Bay–which is in fact just the final extension of the River, being the Susquehanna’s drowned estuary. Since 2022, this blog has celebrated the mighty Chesapeake as the goal of the Potomac River, but I’ve kept in mind this other goal of traveling the source of the Chesapeake, the Susquehanna, whose stream-fed fresh waters mix with the salt of the Atlantic in the 200-mile-long bay.

The Susquehanna watershed, from Cooperstown (top right corner) to the Chesapeake (bottom right corner) (Open Street Map, 2024, and Wikipedia)

The Susquehanna at Harrisburg, state capital of Pennsylvania (Getty Images); the river here is a mile wide and fast flowing

Part of my plan had been to drive along the Susquehanna for as far as I could. On June 8, part of this plan was finally realized as Jean and I drove right beside the river on U.S. Route 15 for 100 miles from Harrisburg, PA to Williamsport, PA. There were almost no buildings between us and the Susquehanna, because the floodplain, which has been frequently flooded over the years, has made building a hazardous venture. So we were able to see the broad and often rock-strewn riverbed and fast-flowing waters through gaps in the abundant woods for most of that distance. A dream come true for me.

But only Part One of our June journey to the source.

***********************************************

Just across the Susquehanna in downtown Williamsport, PA, a 360-degree panorama shows a four-corners bronze tribute to the city, the home of Little League Baseball (June 9).

Williamsport to Cooperstown: Baseball? Yes, But More

Lamade Field, Williamsport, with Pennsylvania mountain ridges beyond (June 9). Every August, the city and stadium are packed with visitors for the international Little League World Series.

Baseball has been a love of mine for almost my entire life, and continues to be a binding force for our far-flung family. The children and now their children have played the game and rooted for their favorite teams. The two Susquehanna towns of Williamsport, PA, and Cooperstown, NY, have been iconic–and ironic–centers for the sport, as neither is close to the urban centers where professional major league teams play. But these two Susquehanna country towns are home to the most revered shrines of those who have played the game over the close to 300 years of its existence in different forms.

In 1939, a local Williamsport baseball enthusiast, Carl Stotz, gathered community support to outfit local boys, ages 8 to 12, with uniforms and equipment, and create teams into a local league, so that these kids could have an organized experience like that of the major league heroes they listened to on the radio but rarely got to see in person. The idea spread to other towns, then other states–then other countries–and Little League Baseball became an international phenomenon, with its headquarters in tiny Williamsport.

Trading Team Pins: When teams from around the world come to Williamsport for the World Series, players exchange their official team pins with one another. This display in the Little League Museum shows an assortment of pins from many years (June 9).

Each August, Williamsport hosts the international Little League World Series, and the usually quiet small city is packed with visiting teams and fans from all over the world. On the day we visited, Lamade Stadium (shown above), where the championship finals are played each year, was hosting a transnational girls all-star team visiting the area.

On to Cooperstown: Source of the Susquehanna and Home of the Baseball Hall of Fame

An aerial photo (no date) showing Doubleday Field, the Village of Cooperstown, and Lake Otsego, source of the Susquehanna

This was Jean’s first visit to Cooperstown, which I’d been privileged to visit three times over the years, and we made the most of the opportunity. We had two main goals:

- to visit the Baseball Hall of Fame, with its three floors of exhibits, which follow the history of the game and show in low- and hi-tech detail the teams, the greatest players, the controversies, the advancements, and all the ways that the sport and culture interweave through the history–and look toward the future

View of the Village main street toward the red-brick Hall of Fame two blocks away, and the hills beyond, June 10, morning

- to walk the Village, sample its shops and eateries, and especially reach the spot where Lake Otsego feeds its water into the quiet stream that miles later becomes the mighty Susquehanna–with my camera at the ready to grasp tiny sightings of the place and its inhabitants.

Just below the lake, a Mallard female herds her 7 ducklings in the Susquehanna stream, as cars pass on the bridge, June 10, afternoon

A small selection of photos, with captions, of our Cooperstown day:

Hall of Fame: Mixed-media poster of Jackie Robinson, who in 1947 became the first African-American player admitted to the major leagues–and so changed the game of baseball and contributed to the necessary advance of American culture. Every year, all teams celebrate April 15, the day he made his Major League debut; on that day, all players wear his Brooklyn Dodgers number, 42.

Hall of Fame: Display honoring the Midwest women’s baseball league during World War II (memorialized in the film “A League of Their Own”)

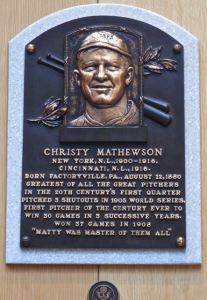

The most hallowed place in the Hall of Fame displays the plaques of all those players who have been voted into the Hall. Here is the plaque of Christy Mathewson, one of the greatest pitchers of all time and honored posthumously as one of the first five inducted into the Hall in 1936.

Life-size basswood sculptures of legendary batters Babe Ruth and Ted Williams in the hall of plaques

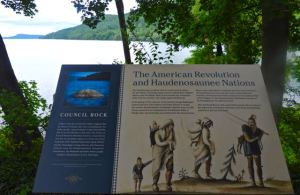

At the joining of Lake Otsego and the Susquehanna, a plaque commemorates the Haudenosaunee peoples, who settled these lands and waterways thousands of years ago. An army of Haudenosaunee fought for the colonists during the Revolution against England–but then were massacred in 1779 by the troops for whom they were fighting. Yet another shameful event in U.S. history.

*********************************************

Ithaca and Serendipity: The Call of Birds

Fall Creek sings beside the Cornell Wildflower Garden, Ithaca, NY, June 11

Just to the north of the Susquehanna watershed and 100 miles west of Cooperstown is Ithaca, NY, home of Cornell University and of the internationally-revered Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which I’ve written about in this blog concerning the annual Great Backyard Bird Count, in which I’ve participated for years, and the Lab’s creation of the Merlin and E-Bird electronic Bird Identifiers–invaluable tools for birders. Needless to say, the Lab was on our must-do list for this PA-NY trip, as I’ve not been there in person before.

African, Australian, and Asian parts of the Birds of the World wall art at the Cornell Lab Visitors Center, June 11

In planning the trip, we’d not known what to expect before we got there, as the website kept saying that the Visitors Center was still being renovated and would be reopened “sometime in the spring.” Here it was June, and no announcement of reopening. “Oh well,” I thought, “there’s still plenty to explore, with the Arboretum, the Botanical Gardens, and the miles of trails.”

But when we reached the Botanical Gardens, I mentioned the Lab to one of the docents, and she fairly shouted, “Guess what! It’s open! Today it’s reopened. Can you believe it?” Talk about serendipity. “Your timing is perfect! ” she said.

A Red-bellied Woodpecker and a Downy Woodpecker at the Visitors Center feeders, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, June 11

So the remainder of our morning was spent at the Botanical Gardens, especially in the magnificent Herb Garden, where volunteers and staff were hard at work. Then, after lunch in Ithaca, we explored the Wildflower Garden and the Arboretum, before heading over to the Lab and the newly-renovated Visitors Center later in the afternoon. A great day, even better than we’d expected!

Panorama of the Cornell Herb Garden, June 11

Red-winged Blackbird in the Cornell Arboretum, June 11

Woodchuck eats and scans the woods along the roadway at the Cornell Arboretum, June 11

Marsh with Water Lilies in the Cornell Arboretum, June 11

Interactive displays engage visitors at the newly-reopened Cornell Lab Visitors Center, June 11

**********************************************************

Amish Country: A Living Past, A Model for the Future?

On the highways through Intercourse, PA, horse-drawn buggies and wagons share the roadway with trucks and cars, including ours, from which I took this photo (June 12)

On the final two days of our journey, June 12-13, we stayed in Intercourse, PA, in the southern part of the Susquehanna watershed. We wanted to stay longer, because the famous Amish culture of this unique region offers such a stark–and pleasant–contrast to the fast, loud, and pollution-intense culture that dominates most of the U.S.

Amish culture dates from 17th century Germany and Switzerland, with adherents to this form of Christian religion first coming to colonial North America in the early 18th century and settling in the Pennsylvania colony because of its reputation for religious toleration. The Amish in the U.S. were almost an exclusively agrarian society, and they continue to be best known for their farms, their closeness to the land, their care of plants and animals, and their rejection of technologies such as electricity, fossil-fueled cars and trucks, and mass communication.

Pony, cart, and driver at a main commercial intersection in the town, June 12

However, as their population has steadily grown (more than 250,000 over 25 states and Canadian provinces) and as available farmland has grown scarcer and much more expensive, today only about 10% of Amish are mainly farmers. Most adults, male and female, find work either in Amish craft businesses or non-Amish service industries–often requiring their communities to make limited technological accommodations, such as work with computers.

But even communities with more such economic accommodations retain their core anti-technological values and practices, as well as their intense loyalty to a community-focused service ethic and plain lifestyles. The signature symbols of the horse and buggy, the communal barn-raising, and the traditional, simple, home-made clothing persist across communities.

In front of the Bird-in-Hand Bakery in the town of the same name, I look across the quiet road to fields with crops ripening, June 13

In our brief two days in the region we were impressed again and again by the beauty, exquisite care, and quietness of the farms we passed and the businesses we visited, at which Amish employees were working. In sharp, jarring contrast was the frequent roar of trucks, from pickups to 18-wheelers, pounding along the highway (PA route 340) that traversed the center of town and links York and Lancaster in the west to Philadelphia and points east. Nothing makes the contrast between cultural visions sharper than when a horse and buggy clip-clops along the highway at 10 MPH and a huge truck, engine snuffling and brakes grinding, slows down then tries to pass (as in the photo at the top of this section).

On PA route 340 in Intercourse, a horse and buggy clips along before a field of cows, and cars approach, June 12.

One is a vision of the present we know all too well in most of the U.S. The other is a vision out of a past that seems stunningly out of place in our present. But must the present vision of ceaseless competition, exhaust fumes, and brain-shaking sound be that of our future? Or can we make more room in our future for a quieter, more nature-respectful, more community-loving vision? A vision that has already been resilient over centuries?

Vision of the future or only of the past? A Cabbage Leaf Butterfly and a farm scene in Intercourse, June 13

*********************************************

The June 2024 Photo/Video Gallery: Potpourri from our Little Lake Community

Jean’s French Gruyere Souffle for Father’s Day, June 16

Fruit breakfast and basil plant, already hot morning, June 23

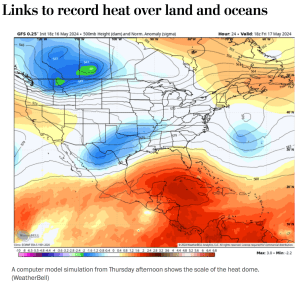

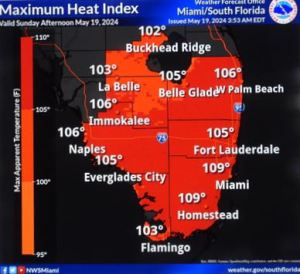

Ripening fast in the high 90’s heat: Allegheny blackberries, north end path, June 22

Tufted Titmouse–usually hiding–perches in the Willow Oak, east bank, June 2

Baby Cottontail feeds on grass and clover, beside the Northwest path, hot evening, June 22

Blue Heron on dam structure, north end of lake, with playground in the background, June 15

Spotted sandpiper–first sighting this far inland!–walks and pecks on the log in the southeast cove, June 2

Like the sandpiper above, another visitor from the coast, an adult Osprey, June 22, on the dead white oak, east bank of the lake

Bumblebee in the air between two Swamp Milkweed, south end shore, June 15

Three baby Green Herons play/fight near the nest, southeast shore, June 15; first sighting in these numbers

Tree Swallow–first sighting here-in the dead Willow Oak, east bank, June 16

Male Cardinal calls and scans on a branch on the southeast bank after sunrise, June 15

View toward downtown with our Goose flock in the lake just after sunrise, June 15

Natural bouquet: Crown Vetch and Daisy Fleabane, new blooms, near the northwest corner of the lake, June 16

Aphrodite Fritillary butterfly as frogs trill and jet sounds overhead, below dam, June 3

Barn Swallow on dam structure, north end, June 3

Blue Heron lands in pine, north end woods, June 2

Bumblebee feeds in Purple Thistle, first bloom of the year, north end, as birds call, June 3

Green heron walks, scans, and preens on log, southwest shore, morning, June 3: perhaps the parent of the 3 babies videoed on June 15?

So many wonderful moments this month, here and in Pennsylvania and New York! Now the heat of summer is upon us, as we head into July. Here’s to more beautiful scenes…