Mockingbird on dry Pokeberry bush, north shore of lake, Nov. 17

In this month’s entry:

Thanksgiving Gifts from Our Family

Wildlife Around Our Lake Disappear in the Ongoing Drought

Election Gives Narrow, But Still Decisive Win to Climate Change Deniers

Keeping Up the Good Fight: Visiting the Virginia State Arboretum

The November 2024 Photo Gallery: Pretty Landscapes, Growing Silence

At nearby Lake Newport, we walk on crispy, fallen leaves amid skyscraping trees and brilliant autumn colors.

Thanksgiving Gifts from Our Family

How fortunate and thankful we are to be able to share our joys with family who have come to join us from New York, Virginia, and Georgia. Our Thanksgiving embraces a week of holiday outings, imaginative meals, and raucous, witty (of course!) conversations among three generations from age 4 to 80. Even those family members we can’t be with in person, we will be with via phone, text, and FaceTime.

What did we do to be so blessed? And, wouldn’t you know it, we’ve even gotten an inch of rain this week to begin, we hope, to make a dent in the drought.

************************************************************************

Green algae thick in the inlet stream into our lake, Nov. 18, as significant rain has not fallen since September

Ongoing Drought and the Fast Spread of Bird Flu: Birds Disappear Here, While Wildfires Plague the Northeast

Exactly one year ago (see November 2023 entry), this blog celebrated in story, video, and photos a profusion of wildlife around our small lake. The stars of the entry were several pairs of amorous mallards happily building their relationships, while the videos featured a varied soundtrack of the many songbirds and waterfowl calling to their fellows in an often rainy setting.

The only ducks we’ve seen in our lake since the spring are these four Buffleheads, who visited last week for one day, and then flew off. Even our frequent cormorants have not visited. Only our resident flock of Canada geese visit this water, and even their visits have declined.

Oh, what a difference a year makes! The drought brought on by record high average temperatures across the country (and much of the entire world) this year has been intensifying in our multi-state region since early in 2024. The drought has continued through this November (October was completely rainless), and this November is the hottest on record in our area (as reported in the Washington Post, Dec. 3). Last month’s entry focused on how quickly the lakeshore’s plants were drying out and leaves were beginning to fall. The music of the birds had almost ceased as birds migrated toward wherever they might find fresh water.

The Next Pandemic? Perhaps Bird Flu. A secondary cause of the bird decline is the H5N1 bird flu, which has spread rapidly across the country, causing the decimation of many millions of chickens in commercial flocks, and now also infecting some 685 cattle herds in 15 states, as reported in the Los Angeles Times (“Business as Usual Despite H5N1,” Nov. 30) and in National Geographic (Fred Guteri, Dec. 18). Unfortunately, like the widespread drought, scant attention is being paid to the spread of this disease in our environmentally-oblivious U.S. of 2024.

Photo: NatGeo/Reuters

No one wants to hear this, because there is clearly no appetite in this country for even thinking about precautions for a new health crisis. But, as Zeynep Tufekci writes in the Dec. 9 New York Times, more and more human cases of H5N1 are arising, and the time is now to take the threat seriously (“A Bird Flu Pandemic Would Be One of the Most Foreseeable Catastrophes in History”). In 2019, there were health experts in the first Trump administration who could push back strongly on the President’s fantasies about COVID-19 (remember the bleach cure and hydroxychloroquine?). But now he has surrounded himself with vaccine deniers like Robert F.Kennedy, Jr., and there will be no medical leaders like Anthony Fauci, Deborah Birx, and Francis Collins to mobilize an effective national/international response, so wishful thinking, studied ignorance, and quack remedies will abound, more like the Middle Ages than the 21st century.

At nearby Lake Newport, the bone-dry inlet stream from surrounding hills and neighborhoods, as the drought goes on, Nov. 20

Wildfires in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts

5000-acre Jennings Creek Fire on New York-New Jersey border (USA Today photo, Nov. 18)

Last month’s blog also displayed the map of the U.S. (created by Drought Monitor), which showed almost the entire nation (except for hurricane-pounded Florida and western North Carolina) in a moderate to severe drought. Wildfires were in lethal bloom in many Western states. Weather Service maps showed “red flag warnings” across much of the central and eastern states, including New York State and even New England.

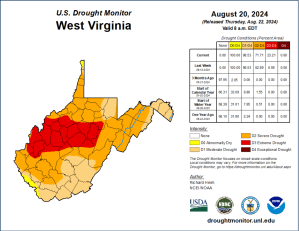

Well, sure enough, in November as many as 500 fires of various sizes have transformed the usually wet and cooling Northeast states into a California-like wildfire season–experiencing such change for the first time in memory. The largest of these blazes so far has been the Jennings Creek fire (shown above): 5000 acres and growing along the New York-New Jersey border, with smoke from all these fires fouling the air in East Coast cities. Meanwhile, in many other states, such as Oklahoma and Texas, drought has caused the massive loss of crops, which this blog catalogued in August as having occurred here in Virginia’s usually lush Shenandoah Valley. Neighboring West Virginia’s governor–a staunch climate-change denier–declared a statewide drought emergency across its 55 counties:

***************************************************************************

Election Gives Narrow, But Still Decisive Win to Climate Change Deniers

To make matters even worse, this November’s closely-contested elections gave a thin, but nevertheless sufficient victory to former President Donald Trump and to just enough climate-change denying Republican candidates to give that party razor-thin majority control in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Trump, who is a strident spokesperson for the fossil-fuel cartel, made “Drill, baby drill!” for gas and oil one of the emphatic slogans of his campaign.

As if that weren’t destructive enough, the rival candidate, Democrat Kamala Harris, never during the campaign spoke out in favor of renewable energy sources, and indeed promised voters in the closely-contested state of Pennsylvania that she supported the destructive, water-wasting practice of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for natural gas, which has become in recent years a favored process of gas extraction in that state and many others. Why she and her party turned their backs on climate is not clear, but surely indicates that they did not trust voters to understand the dangers and their importance. This is puzzling, because, as this blog detailed in July, polls show that a healthy majority of Americans see climate change as a solvable major problem. But at this point, possible solutions don’t even get on the ballot.

So, with no candidates in either party having the courage to speak the truth about climate destruction, the results were inevitable. As the world and our nation become steadily hotter, more polluted, drier, less fertile, and with more extreme storms, we humans are getting what none of us want, but what too many of us prefer to ignore, or deny, or feel powerless to prevent. Too bad that our fellow creatures don’t have a say about our actions, but just suffer–and disappear–through our cowardice.

***********************************************************

Panorama of the Virginia State Arboretum: Cedar of Lebanon foreground, and Bald Cypress grove and famous yellow Ginkgo grove in distance, Nov. 8

Fighting the Good Fight: Visiting the Virginia State Arboretum

The magnificent Dawn Redwood, native to China, 80 feet tall, part of the international display at the Arboretum, Nov. 8

We had read about the Virginia State Arboretum, part of the Blandy Experimental Farm operated by the University of Virginia. We finally visited on November 8, a warm, sunny day just perfect for walking and viewing. Located 80 miles west of us, north of Shenandoah National Park, and just beyond the Shenandoah River near the village of Boyce, the Arboretum is an out-of-the-way miracle that is one of Virginia’s best kept secrets. With trees from around the world and across the U.S., as well as representative trees from throughout the state, the Arboretum’s several miles of trails offer stunning sights, good exercise, and a pleasant education in arboreal beauty.

Visitors to the Arboretum walk the Alley of Cedars of Lebanon toward the Ginkgo Grove, Nov. 8

Our visit came during the Arboretum’s Ginkgo Festival, so about a hundred visitors of all ages had come especially to see the famous grove of Asian Ginkgos (pictured above). Our leisurely two-hour visit also included a walk along the Cedars of Lebanon Alley, a stroll among the many labelled and fragrant plants in the garden of herbs from around the world, and a talk with one of the helpful members of the staff–who answered our questions about the effects of the drought on the trees. She told us that often drought effects on trees are not seen until two years or so into the event, because of the trees’ resilience and stores of nutrients. However, she said, one evident effect already had been the drying up of the ponds and lakes on the property, as well as the decline in the bird population. Nevertheless, the broad lawns were still remarkably green and the trees glowed with fall colors, so the sights were lush and I even was able to get one bird photo, of the Brown Thrasher (below).

Brown Thrasher silhouetted in a berry-covered Buckthorn tree between the Cedars of Lebanon Alley and the Ginkgo Grove, Nov. 8

Greenhouse and outdoor international herb garden, State Arboretum of Virginia, Nov. 8. Ah, the fragrances!

*************************************************************************

Sunrise panorama toward colorful north end woods, with west side dock in middle distance, Nov. 15

November 2024 Photo Gallery: Finding Beauty in the Drought

This month’s Gallery features scenic photos from around our little Lake Cameron, from nearby Lake Newport, and from other local sites. The birds are much fewer in number, so the music of their calls has all but disappeared, though the number of species is still considerable, as the photos here demonstrate. Happily, some still make their presence known visually, and we highlight them here. We give them thanks for sharing their delicate beauty.

Eighteen Canada Geese adorn our lake before the north end, Nov, 23. They’re visiting frequently now, but no longer daily.

White-throated Sparrow, first sighting here of this species after two years of listening to the call, north end path, morning after rain, Nov. 28

Inlet stream to our lake, water clear after night of rain and colder temps, Nov. 28

Flock of Rock Doves on stanchion west of lake, morning after rain, Nov. 28

Burning Bush and gazebo, west shore of our lake, with view toward downtown, morning after rain, Nov. 28

American Crow atop Tulip Tree, north end woods, Nov. 28

Three Turkey Vultures glide above the east bank of our lake, the most we’ve seen here at one time, Nov. 18

Chipping Sparrow in dried Cutleaf Teazel, at the northeast corner of our lake, on a warm, dry morning, Nov. 8

Great Blue Heron, our regular visitor, beside the inlet culvert on the southwest shore, warm Nov. 18

At nearby Lake Newport, homes and fall colors are reflected as we look from the dam on a cold morning, Nov. 20

Meadowlark Botanical Gardens, holiday light show, trees and gazebo illuminated across lake, Nov. 25

Male Cardinal, amid Asters, Boneset, and Blackberry Canes, northeast corner of our lake, Nov. 7

This male House Finch lands atop a Tulip Tree in the north end woods by our lake, on a cool morning, Nov. 18

Bluejay near feeder, east side, Nov. 8

A newly arrived Yellow Warbler perches in the Willow Oak on the east bank of our lake, Nov. 8

Carolina Wren on branch, southeast shore of our lake, windy morning, Nov. 11

Just after sunrise on a cold Nov. 24, Cherry Laurel, red Oakleaf Hydrangea, and the northern panorama of our lake

Panorama toward the south end of our lake and downtown, with contrails, early morning,Nov. 17

One of our Red-bellied Cooter Turtles, on log at the southeast shore, warm morning, Nov. 15

European Starling scans from atop the dead Oak on the east bank of our lake, on a cold dry morning, Nov. 23

Yellow Warbler feeds on dry Cutleaf Teazel in field west of our lake, Nov. 23

Song Sparrow, amid dry blackberry canes, northeast shore of our lake; warm, windy morning, Nov. 17

In our new garden plot in the public gardens in our town, tiny heads emerge in two of our cauliflower plants, warm morning, Nov. 24

A Grey Squirrel pauses on a branch near the west side path along our lake, on a cold morning, Nov. 24

Mist rising at sunrise, beside the north end outlet stream below dam, Nov. 17

Fall colors, including Scarlet Oak along the west side path, warm morning, Nov. 18

Here’s to a happy, fruitful December, which is bound to be interesting!